Love dairy but can't handle the lactose? Your DNA and Gut Health May Play a Role.

Do you suffer from lactose intolerance? You're not alone. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, about 75% of the world's population has a reduced ability to digest lactose. If you're one of those people, don't worry – there may be hope for you yet! Recent research suggests that your DNA and gut health may play a role in your ability to digest dairy products. Keep reading to learn more about this exciting new research and how it could help people with lactose intolerance.

Lactose intolerance is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme lactase, which is responsible for breaking down lactose into glucose and galactose. Lactase production typically decreases as we age, which is why many adults develop lactose intolerance. However, some people are born with congenital lactase deficiency, which means they never produce lactase in the first place.

Recent research has shown that a person's DNA may play a role in their ability to produce lactase. In one study, researchers looked at the DNA of people with and without lactose intolerance and found that those with lactose intolerance were more likely to have a certain genetic variant. This variant is thought to reduce the activity of the lactase enzyme, making it more difficult for the body to break down lactose.

The Science; Primary and secondary forms of lactose intolerance. Hang in there!

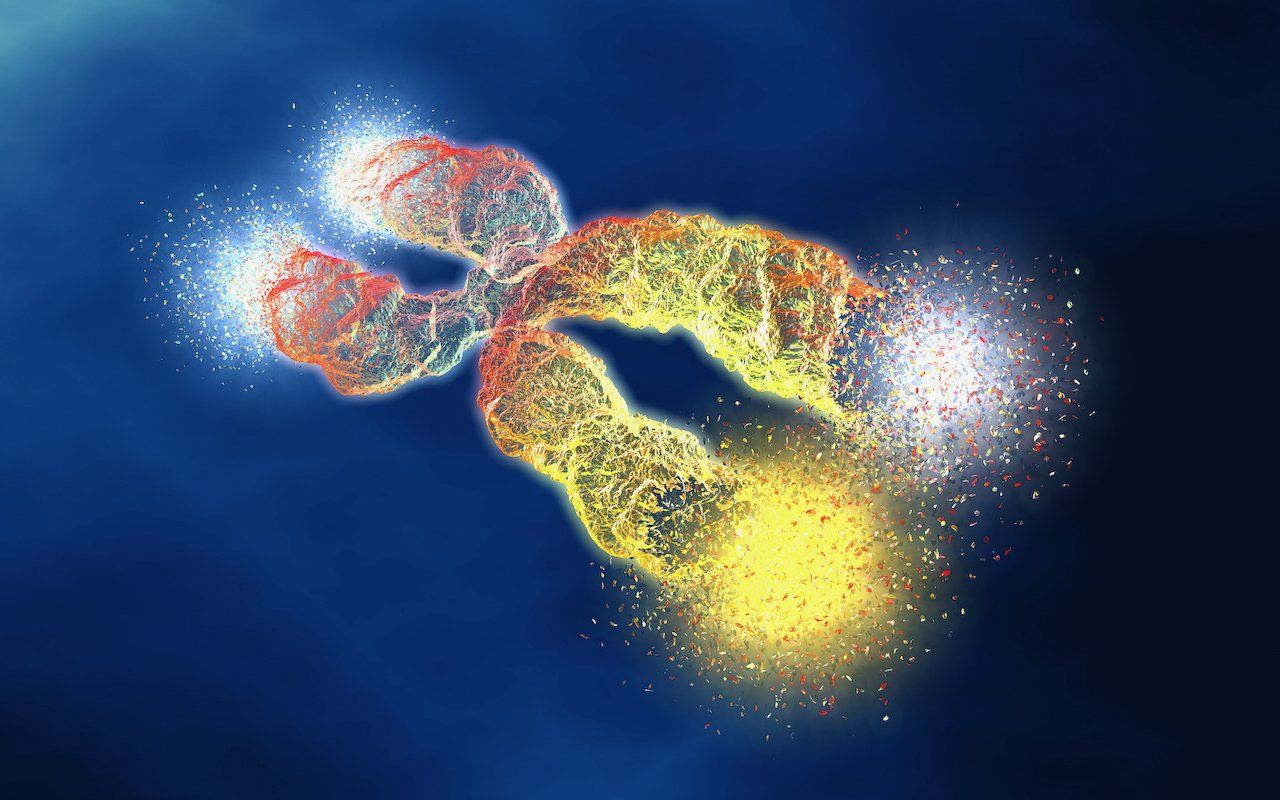

Primary lactose intolerance is due to a genetic mutation in the lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH) enzyme which is encoded by the lactase (LCT) gene and is located on chromosome 2q21. Chromosomes are the structures that carry our DNA (blueprint for life) and each chromosome has anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand genes. The LCT gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called beta-galactosidase. This enzyme is important for breaking down lactose into smaller sugars called glucose and galactose that can be easily absorbed by our gut cells. People with primary lactose intolerance have a mutation in the LCT gene that prevents their cells from making functional beta-galactosidase enzymes. As a result, lactose isn't broken down and absorbed properly, leading to gastrointestinal symptoms. This means that lactose isn't digested and it stays in the gut where it ferments and causes gas, bloating, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.

Secondary lactose intolerance is the more common form of the condition and is not caused by a mutation in the LCT gene. Instead, it's usually the result of another medical condition that damages the small intestine. The small intestine is the part of the digestive tract where most nutrient absorption occurs. The enzyme lactase is found in the small intestine, in the very tip of the tiny hair-like projections called microvilli, on the surface of the cells that line the intestine. Diseases that can damage the small intestine include celiac disease, Crohn's disease, and viral infections such as rotavirus. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) can also affect the small intestine. When the small intestine is damaged, it's not able to produce enough of the enzyme lactase. As a result, lactose isn't properly broken down and absorbed, leading to gastrointestinal symptoms.

Microbiota

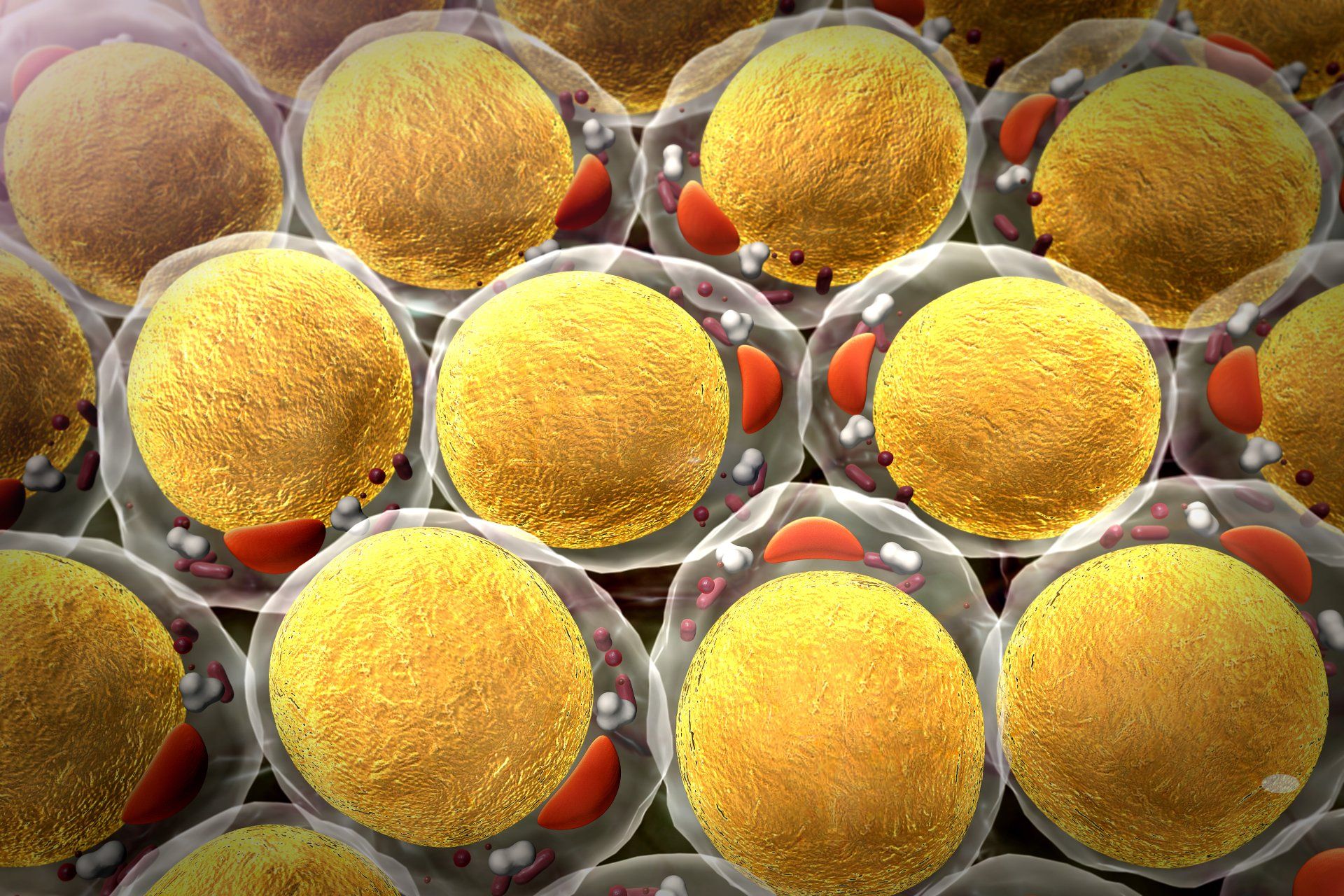

The lining of the gut contains billions of bacteria, many of which are responsible for breaking down food and absorbing nutrients. People with lactose intolerance often have a different mix of gut bacteria than people who can digest lactose without any problems. This difference in gut bacteria is thought to contribute to the symptoms of lactose intolerance. The gut microbiome is like an extension of the human genome. This is because the microbes do many activities that directly affect the gut's physiology, including their ability to absorb lactose and other carbohydrates.

Infants and milk digestion

Many parents are concerned about how much milk their infants will consume. According to research, the enzyme LPH (encoded in the LCT gene ) reaches its peak activity during nursing and decreases its expression after weaning, resulting in lactase non-persistence (LNP) and adult milk and dairy product intolerance. However, a change or mutation that occurred approximately 7,000 years ago in Europe resulted in lactase persistence (LP), which allows people to digest milk. The variant is present in around 35% of the world's population!

Meds

Lactose intolerance can also be caused by certain medications, such as antibiotics and acid-lowering drugs. These medications have the potential to damage the lining of the small intestine, leading to a temporary decrease in lactase production. Symptoms usually go away when the person stops taking the medication. However, before you stop taking any medications, please consult with your doctor.

Lactose intolerance is different from milk allergy. Milk allergy is when your body mistakes milk for a harmful substance and produces IgE antibodies in response.

So, what does this all mean for those who are lactose intolerant? To avoid permanently removing dairy from your diet, it's important to distinguish between primary and secondary lactose intolerance. If you're lactose intolerant, it doesn't necessarily mean that you're allergic to milk or dairy products. It just means that your body can't process lactose properly.

What to do:

There are many things you can do to ease your symptoms.

- You might consider getting a DNA lactose intolerance test and a Functional Medicine evaluation to discover the cause of your lactose intolerance.

- Cut back on dairy: If you're consuming too much dairy, it can cause bloating, gas, and diarrhea. Try cutting back on dairy products and see if your symptoms improve. But for many people, that's not an ideal solution. After all, dairy contains important nutrients like calcium and vitamin D. You could choose to supplement to make up for the absence of dairy.

- Choose lactose-free products: There are many lactose-free products available on the market today. Choose milk, cheese, and yogurt that are labeled "lactose-free."

- Take lactase enzyme supplements: These supplements can help your body break down lactose. Be sure to take them before you eat or drink dairy products.

- Take Prebiotics: Prebiotics can help the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut.

- Take probiotics: Probiotics are helpful bacteria that can improve gut health. They may also help relieve symptoms of lactose intolerance.

- Try fermented milk products, such as yogurt and kefir, which are easier to digest than regular milk. They may also help improve gut health.

- Take broad spectrum digestive enzymes to aid digestion and absorption, while reducing the gut burden. To increase their effectiveness, take them before you eat or drink dairy products.

Conclusion

There's no need to suffer from lactose intolerance. If you're still having trouble managing your symptoms, talk to your doctor or a Functional Medicine Doctor. He or she can help you find the best way to cope with lactose intolerance. You don't have to let it rule your life. With a little effort, you can still enjoy dairy products without discomfort.

Do you have any tips for dealing with lactose intolerance? Share them in the comments below!

If you'd like to learn more about lactose intolerance and gut health, I've recently published a book called "Understanding Genomics:

How Nutrition, Supplements, and Lifestyle Can Help You Unlock Your Genetic Superpowers."

This book is a must-read if you want to learn how to control your genetic destiny!

Order a copy today!

Until then, stay healthy and happy!

Dr. Marios Michael

Resources:

- Dr. Marios Michael, DC, CNS, cFMP, 06/2022, Understanding Genomics; How Nutrition, Supplements, and Lifestyle Can Help You Unlock Your Genetic Superpowers, 1st edition, Austin, Bookbaby.

- Anguita-Ruiz A, Aguilera CM, Gil Á. Genetics of Lactose Intolerance: An Updated Review and Online Interactive World Maps of Phenotype and Genotype Frequencies. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 3;12(9):2689. doi: 10.3390/nu12092689. PMID: 32899182; PMCID: PMC7551416.

https://doi.org/pnas.1803630115

- "Lactose Intolerance." National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 01 Mar. 2017. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

- "Lactose Intolerance." Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 09 Feb. 2017. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

- "Dealing with Lactose Intolerance." Harvard Health Blog. Harvard Health Publications, 23 Dec. 2016. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

- "Lactose Intolerance." WebMD. WebMD, n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

Medical Disclaimer: The information included on this blog is for educational purposes only. It is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice. The reader should always consult his or her healthcare provider to determine the appropriateness of the information for their own situation or if they have any questions regarding a medical condition or treatment plan. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this blog! Reading the information on this blog does not create a physician-patient relationship.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.